IDEAVENTIONS ACADEMY

|

by Liz Crowder, Director of Admissions & College Counseling

“I’m bored.” These two little words strike fear into a parent’s heart. Why? Because we feel like it’s our job to rectify it. While some degree of boredom is good for kids (it helps motivate them to do something about it), at other times, it can signal that intervention is needed. Enter the gifted child. Gifted kids have advanced intellectual abilities and may find regular schoolwork or activities unchallenging, unstimulating, or tedious. So, when they say, “I’m bored,” it could indicate a few things: Intellectual curiosity: Gifted kids have a higher capacity for learning and require challenging tasks or materials to stay engaged, not simply more worksheets or the opportunity to tutor another child who’s falling behind. They want to learn! If you want to learn about astronomy but are given the task of painting the White House, it might not be too bad initially. After all, you’re at the White House! Important stuff happens here! But after the first week of eight-hour days and an eighteenth bucket of white paint, the thrill is gone, as BB King would say. A gifted student might find themselves painting the building with a series of stars, perhaps Orion or Cassiopeia. It’s too easy: When students feel unchallenged, they may express it as boredom. When this happens month after month, their motivation can drop, leading to boredom and frustration. To prevent underachievement, these students need differentiated instruction or more complex tasks. These kiddos are used to doing their work without much (or any) effort. The one skill they develop from this environment is the ability to “call it in.” Only later, maybe in college, do they have to study. It’s a shame to have students wait twelve years or more to feel engaged and learn something. But how many gifted children have dropped out of school before then? It’s too hard: Sometimes students find themselves in academic situations that are more challenging than they bargained for. It may be that they never had to work at learning before or having to spend time memorizing vocabulary for a foreign language is tedious. For them, it may feel like boredom, so that’s the word they use. But actually, they’re finally facing a difficult task. Ask what they find boring about what they’re doing, and the answer might surprise you. It may be that they’re being challenged, a feeling they haven’t experienced before. Loneliness: Due to unique interests, advanced abilities, or feeling that those around them don’t understand them, gifted children may feel isolated. When they say they are bored, it could indicate that they are not connecting with others on a social or emotional level. Finding a school with other intellectually curious kids can help build those social connections. One of the most beautiful phrases from a gifted child’s mouth is, “I found my people!” I can do it myself: Gifted children often have a strong desire for independence and self-directed learning. If they feel restricted or limited in their choices or are not allowed to pursue their interests, they may express boredom. Too often, America’s educational system is fraught with a rigid approach to education with checkboxes to click off. Fortunate are the children who attend schools where a curious class can dive deep into an area of passion beyond teaching for the test. Projects of their choosing or papers on topics of their choice can go a long way toward keeping a gifted child feeling engaged and having a sense of agency in their learning. Screens: Finally, we can’t forget screens. The real world moves slower than a YouTube video or video game. Students who spend a significant amount of time on screens daily find slower-paced activities boring compared to screens stimulation. If you find yourself in this situation, find a week that works for your family, and try a screen-free week. Keep a journal to see how your child feels at the beginning of the week and how that compares to the end of the week. Maybe at the end of the week, they’ll have picked up toys or books that have been gathering dust on the shelves. When a gifted child says, “I’m bored,” it can carry a deeper meaning than simply being bored in the traditional sense. As parents and educators, we need to pay attention to these cues. Addressing unique needs for intellectual challenge, social connection, and autonomy can help prevent gifted children from experiencing disengagement, underachievement, and other negative impacts on their overall development. While many parents and educators might think that gifted kids will be okay because of their ability to learn, they are often at risk for finding stimulation in ways that can be troublesome: drugs, skipping school, and disconnection from education in general. So perhaps when we hear our child say, “I’m bored,” it should strike a little fear into our hearts. And who knows, finding a way to engage them in an area of passion (or even interest) might go a long way toward a happy, productive young adult one day.

0 Comments

I can’t believe that we’re in our last month of the school year. The last two years have felt like both a week and 10 years at the same time - the only way I can describe it is: time warp. As we enter the end of the school year, we begin to think about the summer and our classes for next year.

We love seeing kids return in the fall! Some have grown a foot over the summer, some have matured, and most have wonderful stories to tell about their summer experiences. It’s fun to see what the summer months bring. One of the many things I love about our school is that we get to watch the kids grow up academically year over year. As many of our teachers teach students multiple years, we know where they were in May and where they should be in September. It is always interesting to see who comes back academically after the summer. The “summer slide” is a term we use to describe academic loss students experience over the summer. Curricula that build on itself (e.g., math) is written so that the first unit is a review from the prior year. It is fascinating to watch how every child is different. Some return having learned new skills, others return where we left off, and yet others return having lost a month or two of skills. I do believe that summers are a great time to explore and relax, but also a time to do more than play video games. What kids are able to do depends on many factors, including where they are emotionally, after the last two years. If you’re at a loss for what to do and you and your child have time on your hands, read on. I like to leave time for exploration and fun, so these are recommendations to pick up in the fall where you left off in June and understanding that there are only so many hours in a week, I like to focus on the areas of most impact. Reading: This activity helps kids across the board in humanities, English, science, and math classes with reading comprehension and reading fluency. Whether by Kindle, audiobook, or old-fashioned paperback, there can never be enough reading books that your child is interested in trying. See if they will stretch themselves a little with more challenging books. I like these reading lists.

Math: The Northern Virginia area can be pretty competitive when it comes to math. I am a fan of developing problem solving skills rather than advancing through math curriculum at a pace faster than a child is ready. For problem solving practice I like the following:

Project or activity of your child’s choosing: Whether it’s a list of documentaries to watch, trails to hike, helping out, learning how to cook, tinkering or coding, or picking up a new sport, ask your child if there is anything he/she wants to learn. This activity is about being creative and exploring. Summer is for fun, and I hope that your kids find enjoyment in books and in problem solving this summer! Did you know that Ideaventions has a long history of PreK- 3rd education beginning with the founding of our out-of-school programs in 2010? We pioneered a very successful, multi-year, mini-Einsteins science curriculum and have taught thousands of students to enjoy discovery and exploration. Read on to learn more about how we are bringing this back to our school!

When we decided to expand to high school in 2016, we also decided that our final goal was a K-12 school and that we would add the lower elementary school grades after our second graduating class. We believe in building our school the way you would approach an engineering project - develop the components slowly, improve and modify, and then integrate them together. Well, we’re here! We’re about to graduate our class of 2022 and we are turning our sights to 1st to 3rd grades! Adding the lower grades is different from the high school grades since we can’t add one year at a time, so we wanted to complete our high school program first. We are starting with 1st through 3rd, then we’ll add Kindergarten in two years, which will complete the range of grades from K - 12. We are so excited to begin work with the lower elementary grades and to innovate in education and support our younger curious learners! Our plan had been to announce the expansion in September and decided to accelerate the launch to support 1st to 3rd graders as we know that we can make a difference in these children’s lives and the sooner we open the program, the more kids we're able to help. In the tradition of our upper elementary curriculum, we will continue to provide students the opportunity for:

What does a week look like for our future 1st - 3rd graders?

We agree that downtime during the day is necessary for health and wellness, social development, and set the students up for success in academics. Younger children need even more opportunities for movement and our schedule is designed for breaks and movement throughout the day and throughout the week. I get so excited when I think of each part of the curriculum, which we have been slowly building over the past eight years. The integrated history units where students immerse themselves in world cultures and civilizations and through integrated projects work learn about engineering, art, music, community, and character education. In science, we will draw on our decade of experience in inquiry-based, hands-on learning where our students will continue to experiment in the science lab. As we draw our seventh year to a close we are proud of the strength and challenge of both our liberal arts foundations and how they come together with our engineering and science programs. We are excited to be able to provide these opportunities to 1st to 3rd graders looking for an academic challenge in a caring, hands-on, and creative community. First through third grade applications will be accepted starting on Wednesday, April 27. We just wrapped up one of my favorite activities of the year - course selection. When I think of my experience as a student, it was very different from how we do it at school. My school counselor was there to take my form, and no one advised me on what to take or what that may mean. I selected courses based on what looked interesting, and my parents, not having studied in the US, weren't involved. I loved the few courses I was able to choose on my own - I had fun learning statistics and I really enjoyed my CAD class. I had so much fun learning French all four years and German for one. My goal at the time was to be able to travel through Europe and speak with the people I met. I had English and Spanish down, I could converse in French, I was learning German, and that left Italian and Portuguese to explore.

In college I had so many choices that I hadn't been presented with before, and I would read and reread the Course Bulletin and circle all of the classes that I wanted to take (this is before electronic course selection). I think that there was 10+ years of classes I wanted to take, and I had to condense it down to four years. I continued studying French and German whenever I could, and quickly (and sadly) realized that there were some college courses that I wanted to explore that I was unprepared for. I felt that I couldn't make the time to build the skills in order to not embarrass myself in the class. Mostly, these were writing courses. I didn't consider myself a "bad writer", and in high school I had done great in most of my writing assignments, but problem solving was just easier for me. That said, problem solving classes in college were really difficult and time consuming for me, so writing intensive classes had to take a back seat. Long story short, when we counsel students and their families on course selection, we like to bring up the concept of skill development. There never seems to be a good time to work on a skill that is difficult for a person. When kids are in elementary school, they're too little, they should have fun. When kids are in middle school, it's "the teenage years" and with so much is already going on families adding another stressor is hard to do. Finally, in high school, the thought of college admissions makes students and families nervous to take classes in areas that are difficult. Ms. Sheri, our counselor, does an amazing job of encouraging students to "eat their (skills) vegetables" and sign up for non-preferred classes to build those skills. What does skill development mean? For students heading to four-year universities who want to study one of the pre-professional degrees (engineering, business, pre-med), a natural or social science, or one of the liberal arts, I think of the necessary skills as reading academic texts, reading literature, writing for different audiences (e.g., case studies, history papers, analyses, journalistic writing, etc.), studying for different types of classes, time management, problem solving, and taking notes. Our high-school curriculum as a whole presents the opportunities for students to work on these skills. Learning is a process and one can think of learning as stretching our muscles, and just how muscles are uncomfortable when you stretch them, skill development can be uncomfortable as well. The kids who I have seen be most successful enjoy the process of learning. They want to do well, and grades are not the driver; their grades are a byproduct that follow. They are curious to explore new areas of knowledge and are open to working on skills or exploring new ways to learn. There are different levels at which students can challenge themselves, and we advise them to choose courses to develop their skills and develop breadth. We also share how their course selection may be viewed as part of the college admissions process and a way to explore subjects that may teach them about themselves. Course selection is a multidimensional conversation that works best when viewed from an aspect of exploration of knowledge and skill development.  We just returned from our annual overnight school trip, and it was a fantastic experience. Informal, experiential education has always been part of our school philosophy and since March 2020, we hadn’t been able to fully return to our regular field trips. We knew how important these experiences were for students, and not being able to have one for two years proved to us just how important they were to the fabric of our school. Since our founding, we have had day trips about six times a year and a two-night trip. The overnight trip is particularly important in the social-emotional development of our students. By traveling together outside of school, they learn flexibility, independence, and social skills that can’t be taught in a classroom. Being away for two nights allows our students to bond and create long-lasting friendships. After the trip the school gels into a true community from this shared experience. The health and safety restrictions in the 2020-2021 school year prevented us (and the rest of the world) from regular travel, so we didn’t have our annual overnight or any off-campus field trip. We saw the effect on our students. New students didn’t go through the rite-of-passage overnight trip, and the community building, and social connections forged during school outings didn’t take place. This year, we were determined to bring back the overnight and as the Omicron surge waned in DC and New York, we planned our first overnight trip to New York City for our high schoolers. The experience couldn’t have gone better. As anyone who has chaperoned a group of teenagers on a school trip knows, it is not for the weak, and teens being teens, you know to expect the unexpected. So, I was a little nervous, but excited. It was a resounding success! At large schools, students travel as part of their extracurriculars, e.g., band, Model UN, and sports teams. The size of our school allows us to take our high school and incorporate informal education as part of our formal education for the entire student body. For our “Return to Travel” trip we had a packed three days. Our trip began early Wednesday morning at Union Station (thank you parents for dropping them off so early!). Learning began for our suburban students at 8 am on Wednesday morning as we boarded the Acela to New York. Being high school students who are building college lists, we could experience “distance from home” as our train made stops in Delaware and Philadelphia. Our students were given a VISA Gift Card with a balance that they would use for half of the meals during the trip to practice budgeting, and the first meal was lunch on the train. When we arrived in New York, we practiced “walking in the city” which is different from walking in the ‘burbs, dropped off our luggage in the hotel, walked to the commuter ferry (in unplanned sleet) to Hoboken and learned how to tour a college campus. Before starting the tour, we discussed the college, what to observe, and how to reflect on what we would hear and experience. After a phenomenal student tour guide and great presentation by the Dean of Admissions, we had dinner at the dining hall, where we could experience a slice of college life. We made our way to an off-Broadway show, The Play That Went Wrong, which is delightfully funny! Both mornings, everyone showed up on time to breakfast and was ready to go five minutes before the time we had agreed to leave. We made our way downtown to the Financial District, where we had an informative tour about Wall Street and New York finance. It was personally jarring to me to see how much it has changed since I last spent time there in 1998. In our day dedicated to history, we learned about 9/11, which happened before any of our students were born. As a country, we felt 9/11, but being in New York, where so many innocent people lost their lives, evokes a feeling that can’t be described. Closing the day with Come from Away and the story of the diverted planes on 9/11 to Newfoundland reminded us about the goodness of people. On our third day, we spent our day focused on Engineering, by visiting the Intrepid and the Empire State Building. After miles and miles of walking, they were troopers and were just so happy to be out with their friends. After great programming at both locations, we made our way back to the train to go back home. The trip felt both incredibly short, and terrifically long. We had so much fun that it went by in the blink of an eye, and we were able to accomplish so much that it felt like we’d been there for one week. Throughout our trip we received so many compliments from people about how engaged our students were and how polite and clean they were. We knew about them being polite and engaged but being complimented for being clean and organized was new to us! It wasn’t just one person, but so many friendly New Yorkers went out of their way to let us know how great our kids are. Before leaving, we had prepared them as ambassadors of our school, and they all rose up to the challenge. We were able to see them stand a little taller and come together as a group. Kids who normally wouldn’t have talked became friends. Not having field trips for this long has proved to us the power of informal learning to both engage students in their formal education, but to teach them the critical soft skills necessary for college and for their careers. Next year our high schoolers will not only go on our overnight trip (Boston), but we are launching a new program. The resources in our backyard are tremendous - we live a Metro ride away from Washington, DC, and it’s a shame that as locals we don’t make time to appreciate everything the DMV area has to offer. Therefore, the city will become our classroom. Think of it as Google’s Genius Hour goes exploring. We will not schedule classes on Friday afternoons, so students are able to go out from noon to 5:15 (or later if needed). Students will plan and organize the trips, and a teacher will be there as an adult. We will get to know the many dimensions of DC, Maryland, and Virginia, and I can’t wait to see what innovation or insight comes out of next year’s exploration! P.S. Next month, our middle schoolers return to Chincoteague Bay Field Station for their overnight field trip, and they can’t wait!  A few weeks ago, I wrote about research papers and the writing process. Today I will again write about writing, but a different type of writing - writing fluency and finding your voice. Imagine the scene - you need to write something, and nothing is coming out. You stare at a blank Google Doc and there is no inspiration. Well, that has been me for the past few days. Anything I start writing about pales in comparison to the crisis in Ukraine, so I delete it and say a prayer for the people of Ukraine and for world peace. I can picture teens going through a similar experience as they work on writing assignments that are difficult. Some people love writing, and it comes easily to them, for others it’s more challenging. We are very fortunate to have a high-school English teacher who was trained in the Writing Project, and she has brought her magic to our school. I call it magic because I have witnessed students who struggled with writing for years, blossom in her classroom. I have seen students for whom writing is a non-preferred activity, as well as beautiful, eloquent writers who can manipulate language artistically, become paralyzed as they approach each assignment as if it were an Olympic performance. In Ms. Anne’s classroom students keep a blog about something that interests them. By giving students a choice to write about something they love and are interested in, they find their voice. Not only that, but they also learn to enjoy writing. Through their blogs, our students identify something that piques their interest that they will write about for the year. Since it is a subject that they know about, the writing is not measuring knowledge, it’s a type of journal about something they love. It’s all typed so their hands shouldn’t get tired. In this way, the focus is fluency, and like anything in life, the more you do something, the better you become at it. The goal is to give students an opportunity to write and write often. Through this practice they will become better writers. All that we ask of them is to give the process a chance and to try to open up on paper. “Talk” to the page (or computer) the way you would to a friend. And if you have a hard time getting started, set a timer, and just write for that period of time. It doesn’t have to be perfect, and it doesn’t have to be error free. There is no judgment, just effort, and it’s about something you like. The objective is to get your thoughts on the page. I have used this same technique in the Economics class I teach. As I tend to work with 10th and 11th grade students, they have already had Ms. Anne for at least a year. I reserve a few class periods each year for current events. We read an article from the Wall Street Journal related to what we are studying in class, and then we “write a response.” Students are used to having prompts to answer, but I want them to get used to formulating opinions and working in ambiguous, open-ended situations as we mirror what the professional world is like. Usually, the ones who struggle most with this type of assignment in my class are my high achievers, and they want to know the rules in order to do well. My response is usually the same, pretend you are in Ms. Anne’s class, and just write for the next 15 minutes. I just want to know what you’re thinking. We’ll go from there. There’s no right or wrong. So, for this week’s post, that’s what I did. I have pretended to be a student in Ms. Anne’s class, and I have “just written” for 30 minutes. Next time your child is struggling with putting something down on a page, ask them to tell you about something they love - be it a video game or a friend. As they start telling you about it, ask them to write it (type it) for you for five minutes. If you’re curious about some of our students’ blogs - here are some of the ones that were published externally: MOEMS, AMCs, and MATHCOUNTS - those are the three math competitions that our lower school students participate in as part of their math class. For most new students to the school, that first math competition is quite more difficult than they anticipated. Even though we let them know not to expect 100% or that it’s different, it’s still a shock when they earn a 2 out of 5 on the MOEMS or an 8 out of 25 on the AMC 8.

We tell our students not to worry about how they do, that a 2 out of 5 is great for a first attempt in a MOEMS competition, and an 8 out of 25 for an AMC is also great! We’re looking for improvement over time, and the problems are difficult and like problems they are not used to solving. The problems between the three competitions are also different and challenge different skills. Speed matters with the AMC and MATHCOUNTS competitions, whereas speed is not a critical component of MOEMS. Some of our students expend significant effort working to move as quickly through the math curriculum as possible. They view it as a ladder to climb to get to a certain level of math by a certain age. When speed through the math curriculum is achieved through significant effort, we prefer that a student meander a bit and explore the world of competition problems. For students for whom there is a gap in the level of math curriculum, and their competition results, we find that high-school math and science classes are difficult. We have seen that when achievement in competition problems is consistent with the achievement in the curriculum, students are better prepared to manage the complexity of their math classes in high school. I recently watched a sweet video about two hypothetical children, one who has had practice learning how to learn, and one who hasn’t had that experience. This video spoke to me on so many levels as I saw the struggles that many of the children that I have worked with have experienced. I love math competition problems because it forces students like Susie to stop and struggle with problem solving. The benefits of learning the skill of how to learn is applicable to more than math. For our students, where math is traditionally a strength, this gives them the perfect opportunity to practice learning, practice being uncomfortable, and practice not intuitively knowing the answer. How to Practice So, can you practice for the competitions? Yes! For MOEMS, there are practice workbooks with problems like the MOEMS competitions. For parents it is something that kids can work on on their own. The answers are in the middle of the book so that the child can check his/her own work. If they get the problem wrong, then they can go back and rework the problem and check their work. If after reworking it, they still don’t understand, they can go to the back of the book and read the solution. After reading the solution, I recommend trying to resolve it again without looking at the solution. Art of Problem Solving also has Beast Academy, which is an online program that also has the option of books. The problems cover more curricular material, and logic. For AMC and MATHCOUNTS, there are past exams that students can take and practice. Goal Setting I think of math competitions the way I think of sports. In this week of the Winter Olympics and the Super Bowl, I see athletes compete at levels that I can’t imagine, and it looks doable when watching it on TV - that is until I strap on the skis and fall all the way down the hill or imagine a 280 lb. man running towards me with the objective of knocking me down, for fun. The athletes we cheer on TV started somewhere, and it was fun. They also worked hard, training, competing, and pushing themselves. For students and math competitions, I would like students to treat the competition like we do sports. I once heard a fencing coach, Bill Grandy, give the best advice as kids were determining whether to compete for the first time, “You have to set goals. If you walk into that first meet and your only goal is to win, then you’re not ready to compete. Set smaller goals that are challenging, but doable.” For a student who has never practiced or taken a math competition test before, walking in and expecting to get a perfect score is the equivalent of winning the fencing meet. I would love to see students participate in the first competition and use that as a baseline, then determine their goal for the following year. Goals could be, improve my score by 3 points or have enough time to try all of the questions. The goals should be based on how much time they plan on practicing. This practice will not only also translate into a different type of understanding of the curricular material, but will also help students with reading comprehension, speed, and creatively thinking about math problems. Additional Resources Do you want to read more? Here are some additional resources that I have found helpful:

Student math work Student math work The teaching of math is fascinating. It is fascinating and complex. More than any of our other content areas, we have learned so much from our journey. A few years ago, at an MIT Club dinner, the gentleman next to me asked “Have you figured out how to teach problem solving?” My answer was quick, and I was excited to hear his response, “No, not yet, do you know how?” Alas he didn’t, and it led to a fun conversation about the teaching of math. Problem solving is at the core of math, and we’re still working on figuring out how to teach it to a broad range of students. Our experience has been illuminating, and a fun challenge to tackle. When we designed the school, we read the research and work done by Patrick Suppes at Stanford University’s EPGY and by Julian Stanley at Johns Hopkins’ CTY to inform our approach that allowed students of varied math levels to progress at their own pace so that they could reach mathematically challenging material that would keep them engaged. Math, unlike other subjects taught in school (with the exception of foreign languages), builds on itself and requires a mastery of prior material to fully understand the new material being presented. In theory, self-paced math using adaptive technologies appears as a perfect solution. In practice, we found that it works for a smaller percentage of the population than we expected from the research, and even for those students for whom it works, they prefer the interaction with a person. The beauty of our school being a 4th-12th school is that it’s like a longitudinal study; You see how choices made in elementary years affect performance in high school. Here are some of our findings:

For today, I will expand on this last bullet point, and we’ll visit other learnings in later posts. We have found some common areas of struggle in math which include computation errors, copying mistakes or not showing work, anxiety and freezing when working on a problem, and not understanding what the problem is asking. This is not an exhaustive list, and each could be the subject of its own post, but we’ll briefly explore each one.

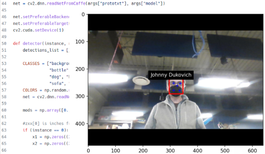

An observation in teaching that took me by surprise, that shouldn’t have, is that I always need more time. I feel that I could fill an entire year of school with just one area of exploration, and we could have great fun exploring. Next year, we are adding an extra math period for math that will give us time to explore additional topics not covered in elementary and middle-school math curricula, such as set theory and proofs. That extra time is also being built in so that students have an opportunity to explore how they learn math. See you next week as we continue to explore math!  Feedback on a student paper Feedback on a student paper About six years ago, I took my son to a summer seminar about The Lord of the Rings. What greeted me (ahem, us) were hundreds of books related to J.R.R. Tolkien. There were the books he wrote, books he read, books about the books he wrote, books about his invented languages, books about his life, books about Oxford, books about the Inklings, and many more books. It was at that moment that I wondered, “Why does my son get to have all of the fun, while I sit at the local Starbucks working while I wait for him?” Being a teacher, I knew that having an adult in a class can offset the balance of a class, but it never hurts to ask. See, I love books. I love books, shoes, and purses, in that order. I couldn’t walk out when all of these books were there and were going to be explored -- without me. After quickly figuring out that I could do the work I was supposed to work on at night, I asked my son if it was ok if I asked to sit in the class (I didn’t want to embarrass him) and when he agreed, I approached the teacher. I told the teacher that I would pay for my registration, and I promised to not say a word. I just wanted an opportunity to sit in a corner in the back of the room and learn. I promised to be a really good adult. Let’s just say that the class did not disappoint and after learning what is philology, I am now a proud owner of a 20-volume set of the Oxford English Dictionary, which I have been able to collect as libraries have sold off their copies. If you know Tolkien, you know why that is relevant. That teacher was Mr. Gardner, who is now one of our high school history teachers at Ideaventions Academy. After sitting in that Tolkien class, and the next one he taught on the Vikings, I realized that I had a gaping hole in my education. I enjoyed history when I was in middle school but did not take any history classes in college because I was afraid of taking the academic risk. The level of academic writing required in college history classes was too intimidating. I didn’t want this for our students, and we are so thankful that Mr. Gardner agreed to come and share his expertise, knowledge, and passion for history with our students. Why research-based history papers? We believe that learning how to write research papers is a multiyear process and no student shows up in high school or college knowing how to write one. It is our job as educators to expose students to long-term assignments where they are challenged to write a variety of papers, and history is a content area where they can develop the skill of writing research papers. As a math and science school with a fair number of students who aspire to be engineers, we emphasize the importance of being able to communicate both orally and in writing. As students enter high school, we invite them to challenge themselves by taking one of our intensive history classes, where they will experience the conditions to develop grit and practice perseverance. Students in this class are exposed to college and post-college level texts, learn how to pick a topic, learn how to form a thesis, learn how to read complex texts within a timeframe, and learn how to write a paper that is organized, tells a story, and uses precise language and dates. The class itself is split into two sessions - the history lesson and the writing workshop. In the history lesson, students are learning about the history that we are studying that year. The papers are done outside of class and use what they are learning in class as a way for students to figure out what area of what we’re learning about they will focus on in their paper. The writing workshop is where we work together on selecting a topic, finding books and journal articles, as well as reviewing outlines and drafts, if ready. In the writing workshop we introduce students to Turabian’s Student’s Guide to Writing College Papers, we hold technical lessons on the Chicago Manual of Style and learn how to footnote a paper. Through discussions, we also learn what goes in the body of the paper, or what is better suited for an appendix, and continue building our glossary of “vague words” that may not be used in papers turned in for this class. How do we do it? It’s a tricky dance between high standards and encouragement and support. The assignments include two short papers and a term paper each semester, and the topics include a critical book review, biographical essays, thesis-based research papers, and analytical essays. We like to give students a guided choice in determining what or who they will write about, as we have found that if a student is interested in the topic, they will be more motivated to work on their papers. The paper is the final product, and part of what we teach students through working on these long-term assignments is how to plan and manage their time by providing long-term deadlines with the scaffolding of intermediate deadlines. We break up the assignment into two intermediate deadlines, topic selection and outline, with further suggested deadlines. We also recommend dates for when a first draft should be complete, but it is a suggested date, rather than a required date. The Engineering Design Process in a History Class What I have learned in teaching students how to work through this process is that it is a process broken down into subprocesses, and this process has many similarities to the engineering design process or the scientific method, which is a description our students understand. Brainstorming: In picking a topic and researching sources, students start by brainstorming ideas for their paper. They then determine the feasibility by researching the available sources and evaluating whether the topic is too broad or too narrow. Research: The reading and research phase is probably one of the areas where the most experimentation happens in class. Some students spend substantial amounts of time reading and taking copious notes, running out of time. Others barely take notes, then have to spend hours rereading. We learn that different types of notes work for different types of topics. We have experimented with highlighting, summarizing reading sessions, taking notes on post-it notes, taking notes on note cards. It’s a messy process and yet, we learn so much. Design: Finally, students get to the point where they organize their notes into an outline. They learn that the title is more important than they realized and that everything in the outline needs to support the title and their thesis. They learn that the organization of an outline will help them tremendously when writing the paper - spend some time on the outline (design) and the implementation (writing) will be faster. Early on some students try to take shortcuts and try to write the outline while still reading based on what they think they will find. They also learn that there is a balance between an outline that is a collection of detailed notes (too detailed) and an outline that was thrown together 30 minutes before the due date (not enough detail). We also can’t forget to think about the introduction and the conclusion. Implementation: Now, we finally get to writing the paper (implementation). Many people would be happy writing that first draft, and turning it in. We ask students to work through multiple drafts and classmates who have taken the class before share techniques that they have learned. To encourage working through the process rather than the grade, we allow students to submit a rewrite of their paper and earn an A- if they weren’t happy with their first grade. Testing and Iterating: Students who take us up on the rewrite, apply the feedback that they receive, and learn from it, begin to see improvements in the next paper. The feedback they receive is extensive, and students learn that red ink is not a judgement on their writing or their worth as a person but take it as coaching and feedback meant to help them grow academically. When we explain that a teacher will only spend that much time giving feedback, it’s because he cares. In this dance of excellence and support, we also allow students to drop the lowest grade for one of the short papers. We ask students that take the intensive history courses for at least two years to compare their papers from the end of year two to the first paper they wrote. They are shocked at how much they have grown. One student said, “That first paper was embarrassing.” They also experience how much faster they become at writing papers and learn about themselves as researchers and writers. The papers are also not as scary as they were at first. I wish all students in high school had the opportunity to spend this much time learning how to research, write, and communicate. “There will come a time in most students' careers when they are assigned a research paper. Such an assignment often creates a great deal of unneeded anxiety in the student, which may result in procrastination and a feeling of confusion and inadequacy.” - Purdue Online Writing Lab Our goal is for that time to be in high school and through the support afforded at a school like ours, to avoid the feeling of inadequacy, and build a feeling of empowerment and confidence. If you want to take a look, here are papers that students wrote about The Great War and World War 2 and compiled them into a website. We're still working on sharing the writing from other topics from 2000+ years of history that we have covered in our classes. In the meantime, enjoy reading what our students have written about this particular time in history.  Once upon a time there was a 20-year-old who walked into a lab and saw robots wandering around a hall and couldn’t believe what she was seeing. That was me walking into the Artificial Intelligence Lab at MIT towards the end of the AI Winter of the 1990s. I remember using what I knew about Scheme to start working on a project in LISP and being intimidated by the knowledge of the people I was working with. Fast forward 25 years, I’m now amazed to see how far the field has come, and to see those robots in homes and at school. Building upon deep and rich experiences in computer science, when our students start 11th grade, another beautiful stage of development becomes apparent. They’re more self-assured, their discourse is elevated to a new level, and their ability to tackle complex systems expands. Now is when we couple Engineering, Mathematics, and Computer Science together in our Artificial Intelligence classes. Students have been introduced to Artificial Intelligence topics in their computer science classes in Lower School and through electives like Self-Driving Cars, which prepare them for the topic of today's post, the capstone courses in AI. In the Artificial Intelligence Research Lab our students learn concepts from the various fields of artificial intelligence, including practical exercises using graphics processing units (GPUs), and experimenting with parallel computing. We introduce them to topics in machine learning such as learning theory, data preparation, supervised and unsupervised learning, computer vision, parallel computing, and convolutional neural networks. Using various real-world applications focused on computer vision, our kids are introduced to topics about the theory and practical algorithms for machine learning using Python and libraries such as TensorFlow, Keras, and OpenCV and parallel computing technologies, such as the CUDA platform. While they are learning these technologies and working on smaller projects, we work across the curriculum in English class where they learn to write a funding proposal for their year-end project while reading about the history of Artificial Intelligence. And, as part of their projects, students learn how to use current technologies, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), to store and manipulate their data sets. The course involved an AI Review Committee made of CTOs at AI companies, practicing professionals in AI, and an AI professor from George Mason University. The students presented to the committee at two points: 1) at the proposal stage for approval and funding and 2) project completion; an experience that provided real-world experience. A second course, which we are piloting this year, is the Autonomous Cognitive Assistant Lab. Autonomous Cognitive Assistant is a machine learning and data science, college-level course that leverages the course curriculum developed at MIT's Beaver Works Center to implement audio, vision, and natural language processing projects. This fascinating course, which also uses Python, also teaches just-in-time math concepts such as linear algebra and Fourier transforms. What differentiates our classes from others that I have seen that introduce students to Artificial Intelligence is that our students develop their own code to implement their projects. In both courses, students spend the second half of the year on their capstone project, where they are able to implement a project of their own. Using the engineering design process, they define a real-world problem to solve or address, then design and implement their solution. In addition to their implementation, students learn how to document a project proposal, document their analysis, conduct testing, and write a final report and poster that they use to present to an external audience and members of the school community. The classes are open to juniors and seniors who have taken AP Computer Science, and when I watch the students present their work, I’m amazed at how far they have come from the young children who I met many years before. These cross-curricular projects bring together years of education in engineering, computer science, math, science, and English, with real-life lessons in project planning, communications, presentation, and problem solving. I can’t wait to hear from our graduates about the work they go on to do not only in college, but also when they enter the workforce. I’m thankful for the educators, Mr. Ryan, Ms. Emily, Mr. Johnny, and Ms. Anne, who have been willing to learn, experiment, and innovate with the kids in order to teach the current technologies of the field, as well as for the experts from both academia and industry who have donated their time to evaluate our students' proposals and presentations so that our future engineers and computer scientists have an opportunity to present their work and obtain authentic feedback. |

AuthorJuliana Heitz is co-founder of Ideaventions Academy and is very excited to share the thinking behind the Academy. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

Copyright © 2010-2024| 12340 Pinecrest Road, Reston, Virginia 20191 | 703-860-0211 | [email protected] | Tax ID 27-2420631 | CEEB Code 470033

RSS Feed

RSS Feed